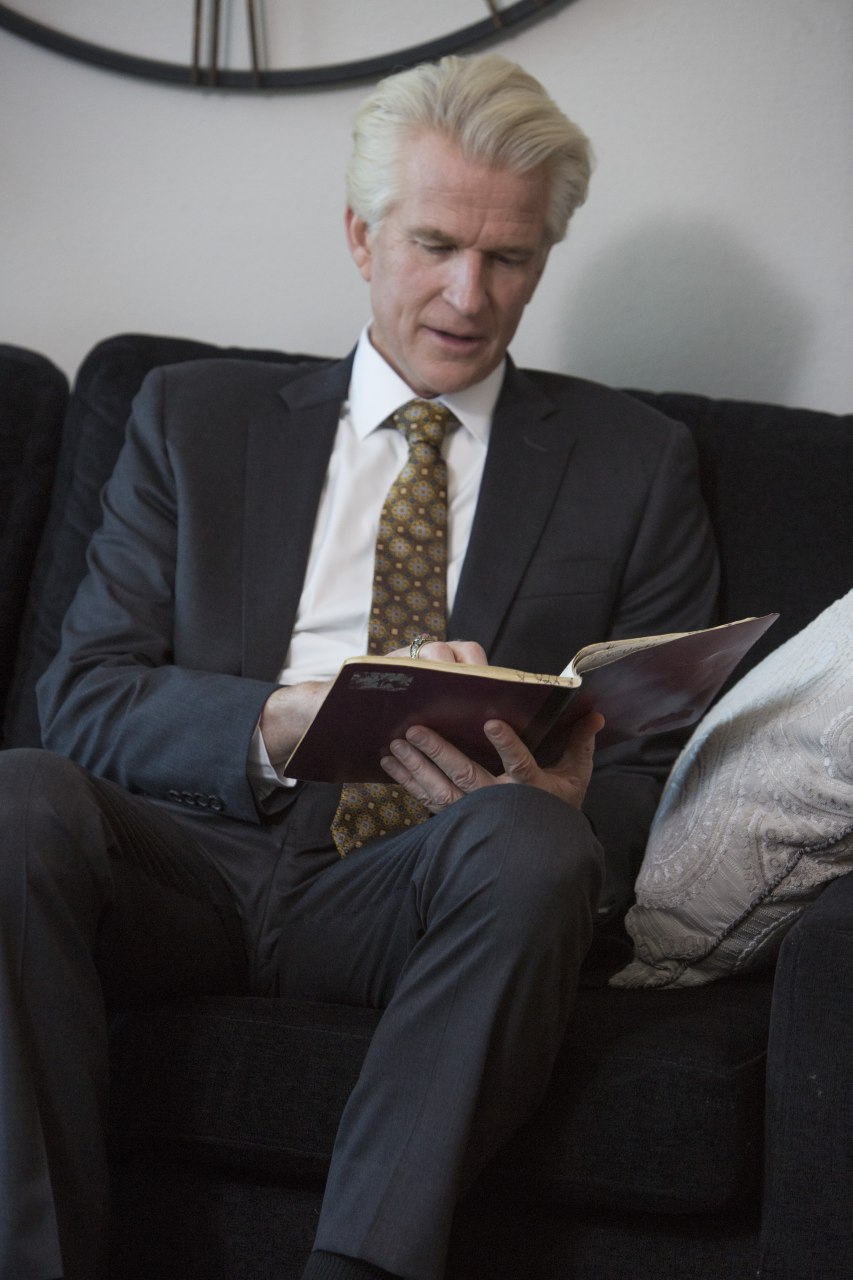

A pulse-pounding cinematic legal drama

that activates reform against corruption in

foster care

The Latest

From Reel to Real

Step up to help thousands of foster kids.

Scroll

The foster care crisis in America: profiting from the lives of children

American children are in the foster care system at any one time.

“The very agencies charged with and paid to keep foster children safe too often failed to provide even the most basic protections, or to take steps to prevent the occurrence of tragedies.”

US Senate Committee on Finance

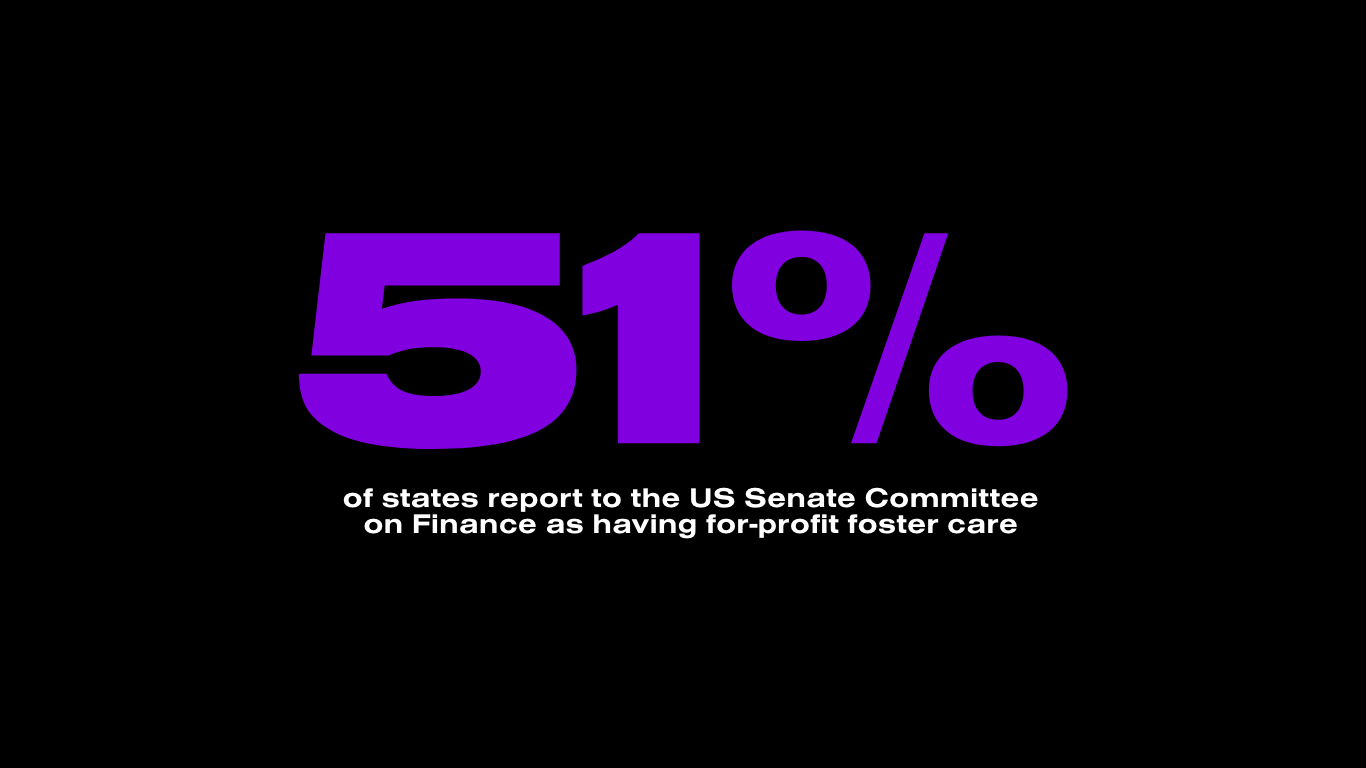

The abuses portrayed in Foster Boy are not imaginary. In fact, they are drawn directly from the experiences of children in the for-profit foster care system – a system within which foster children have been abused, neglected, and denied services, according to a 2017 investigation by the US Senate Committee on Finance. In their words: “The very agencies charged with and paid to keep foster children safe too often failed to provide even the most basic protections, or to take steps to prevent the occurrence of tragedies.” Foster care run for profit is permitted in the majority of the states reporting. Foster Boy seeks to throw light on the outrages of this little-known system – and create momentum for urgent corrective action by communities, states, and the federal government.

At the same time, Foster Boy offers a window into life as too often experienced by foster children today in all kinds of settings – lives that, while often hopeful, also are marked by instability, uncertainty, and a failure to prepare them for the inevitability of aging out of the system into adulthood.

It is well-documented that young adults formerly in foster care suffer unemployment, homelessness, and incarceration to a degree far exceeding that of young adults generally. Foster Boy‘s call to action is to care deeply about these children on the margins of our daily lives, to lend our support to efforts to ease their burden today, and to better equip them for secure and fulfilling lives beyond foster care.

“In some homes, there was sexual, physical, or psychological abuse; in others, love… But it almost didn’t matter, because nothing ever lasted.

Even when we found a good foster home, we didn’t know how to love them or let them love us, and we were never given enough time to learn. We were never taught that we deserve to be cared for and protected and we should have been able to expect at least that.”

Tiller, First Star survey of foster youth

What is foster care?

Foster care is the temporary placement of a child into a new home because of concerns for their safety. In this system, a minor becomes a ward and is placed in an institution, a group home (typically including six or more foster children), or a private home with a certified caregiver known as a “foster parent.” Caregivers are compensated for child-related expenses. The placement of the child is normally arranged by the government or a social service agency.

Why does a child enter foster care?

A child enters foster care when the state determines there are concerns for their safety because of abandonment, abuse and/or neglect (neglect is the reason in 70% of cases). Contrary to popular belief, children in foster care are rarely delinquents and in virtually every case the child is removed from their original home through no fault of their own. In rare instances, children are placed in foster care following the deaths of their legal guardians when there is no extended family to care for them.

What is the “for-profit” foster care industry?

In the “for-profit” foster care industry, for-profit companies procure contracts to manage foster care placements from state and local governments. Like most for-profit corporations, these companies act primarily in the interest of their shareholders. A consistent failure by many “for-profits” and “not-for-profits” to follow established guidelines and the DCFS rules and regulations has resulted in abuse, physical harm, and even death for children in the system.

Take

Action

Now

Want to make a difference? We’ve got a bunch of great ideas to get you started. Just click Act to do your part.

First Star, a national public charity, improves the lives of foster youth by partnering with child welfare agencies, universities, and school districts through innovative college-preparatory programs that ensure foster youth have the academic, life skills, and adult supports needed to successfully transition to higher education and adulthood.

Children’s Advocacy Institute, University of San Diego, California’s premier academic, research, and advocacy organization, seeks to improve the lives of children and youth, with special emphasis on improving the child protection and foster care systems and enhancing resources available to youth aging out of foster care.

Here you can create the content that will be used within the module.

1. The Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS) Report, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau, available at http://www.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/cb/afcarsreport21.pdf (September 30, 2013).

2. National Center for Education Statistics, Digest of Education Statistics: 2012 (table 8), available at http:// nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d12/tables/dt12_008.asp?referrer=report (2012).

3. Foster Care by the Numbers, Casey Family Programs, Sept. 2011, available at http://www.casey.org/media/ MediaKit_FosterCareByTheNumbers.pdf

4. U.S. Census Bureau. Detailed Years of School Completed by People 25 Years and Over by Sex, Age Groups, Race and Hispanic Origin; 2014. Current Population Survey. 2014 Annual Social and Economic Supplement. Calculated by dividing estimated number of inmates, 231, by the confined population of 100,000. See Todd D. Minton, Jail Inmates at Midyear 2013 – Statistical Tables, U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, May 2014, available at http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/jim13st.pdf.

5. Courtney, M., Dworsky, A., Brown, A., Cary, C., Love, K., Vorhies, V. (2011). Midwest evaluation of the adult functioning of former foster youth: Outcomes at age 26. Chicago, IL: Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago.

6. Calculated by dividing the estimated homeless population of the U.S. over the course of a year (1.3 – 2.3 million) by the estimated total population in the U.S. (312,152,633). See Nan P. Roman & Phyllis Wolfe, National Alliance to End Homelessness, Web of Failure: The Relationship Between Foster Care and Homelessness 4 (1995); The Urban Institute, Millions Still Face Homelessness in a Booming Economy, http://www.urban.org/publications/900050.html (2000) (last revised in 2010); U.S. PopClock Projection, http://www.census.gov/popclock/ (last visited Aug. 5, 2014).

7. Calculated by finding average of unemployed former foster youth males (60%) and females (62%) at age 19. See Hook, J. L. & Courtney, M. E. (2010). Employment of Former Foster Youth as Young Adults: Evidence from the Midwest Study. Chicago: Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago.

8. Calculated by finding average of unemployed former foster youth males (54%) and females (53%) at age 24. See Hook, J. L. & Courtney, M. E., Employment of Former Foster Youth as Young Adults: Evidence from the Midwest Study. Chicago: Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago (2010).

9 Fostering Success in Education. National Factsheet on the Educational Outcomes of Children in Foster care. (January 2014).

10. Calculated by finding average of unemployed former foster youth males (54%) and females (53%) at the age 24. See Hook, J. L. & Courtney, M. E., Employment of Former Foster Youth as Young Adults: Evidence from the Midwest Study. Chicago: Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago (2010).